The menstrual cycle: an athlete’s guide

Introduction

Whilst women are biologically identical to men in many ways, there are some fundamental differences. As a male coach I know that to coach women effectively I need to be aware of those differences. This blog is a summary of my research into the menstrual cycle along with some practical recommendations for athletes.

Unfortunately the vast majority of scientific research has been conducted on men and the results ‘scaled-down’ when applied to women. As Dr. Stacy Sims, exercise physiologist specialising in sex differences says, “Women are not small men!”

There are clear differences between men and women which affect how they respond to exercise. For example:

- Women tend to be shorter and have a higher percentage of body fat.

- Strength relative to body mass tends to be lower at around 70-80% that of a male.

- The major organs used in exercise (heart and lungs) are smaller.

- Women burn more fat than carbohydrate compared to men.

- Women have periods!

Most of the sex differences above leave women competing in endurance sports at a slight disadvantage to men (around 10% at Olympic level), particularly in events of shorter duration. The last point however, and the one I want to focus on here does not. Although the large hormonal fluctuations experienced by women represent a challenge to the female athlete there are ways to mitigate the effects and optimise training around a woman’s cycle.

Contrary to popular belief, having a period on race day could actually be an advantage. This is because the hormonal balance on day 1 of the menstrual cycle is most conducive to a good sporting performance. Paula Radcliffe broke the marathon world record in 2002 whilst having menstrual cramps.

Women have much greater energy availability and therefore respond better to training in the early days of their cycle. Conversely training will feel hardest in the premenstrual period due to poorer thermoregulation, low blood sugar levels and less efficient breathing.

That’s not to say women can’t perform during the premenstrual period. Studies have shown that performance markers like VO2 max and lactate threshold remain constant throughout the menstrual cycle.

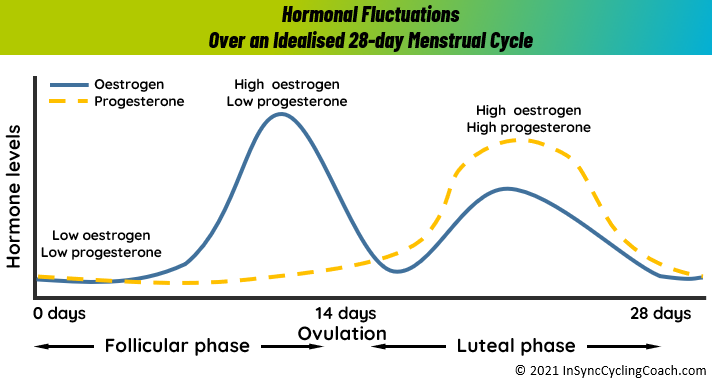

Before we go into the various effects on performance and how to cope with them, here is a reminder of what actually happens during the menstrual cycle.

The Menstrual Cycle

The average menstrual cycle is 28 days long, although it can vary from 21 to 35 days and doesn’t always last the same duration every month. The four main phases of the menstrual cycle are:

- Menstruation

- the Follicular phase (days 1 to 14)

- Ovulation

- the Luteal phase (days 15 to 28)

Menstruation (or Period)

Menstruation is the elimination of the thickened lining of the uterus (endometrium) from the body through the vagina. Menstrual fluid contains blood, cells from the lining of the uterus (endometrial cells) and mucus. The average length of a period is between three and seven days.

Follicular phase

The follicular phase starts on the first day of menstruation and ends with ovulation. Prompted by the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland releases follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). This hormone stimulates the ovary to produce around 5 to 20 follicles (tiny nodules or cysts), which bead on the surface.

Each follicle houses an immature egg. Usually, only one follicle will mature into an egg, while the others die. This can occur around day 10 of a 28-day cycle. The growth of the follicles stimulates the lining of the uterus to thicken in preparation for possible pregnancy.

Ovulation

Ovulation is the release of a mature egg from the surface of the ovary. This usually occurs mid-cycle, around two weeks or so before menstruation starts.

During the follicular phase, the developing follicle causes a rise in the level of oestrogen. The hypothalamus in the brain recognises these rising levels and releases a chemical called gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH). This hormone prompts the pituitary gland to produce raised levels of luteinising hormone (LH) and FSH.

Within two days, ovulation is triggered by the high levels of LH. The egg is funnelled into the fallopian tube and towards the uterus by waves of small, hair-like projections. The life span of the typical egg is only around 24 hours. Unless it meets a sperm during this time, it will die.

Luteal phase

During ovulation, the egg bursts from its follicle, but the ruptured follicle stays on the surface of the ovary. For the next two weeks or so, the follicle transforms into a structure known as the corpus luteum. This structure starts releasing progesterone, along with small amounts of oestrogen. This combination of hormones maintains the thickened lining of the uterus, waiting for a fertilised egg to stick (implant).

If a fertilised egg implants in the lining of the uterus, it produces the hormones that are necessary to maintain the corpus luteum. This includes human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG), the hormone that is detected in a urine test for pregnancy. The corpus luteum keeps producing the raised levels of progesterone that are needed to maintain the thickened lining of the uterus.

If pregnancy does not occur, the corpus luteum withers and dies, usually around day 22 in a 28-day cycle. The drop in progesterone levels causes the lining of the uterus to fall away. This is known as menstruation. The cycle then repeats.

Tracking your cycle

Few female athletes track their cycle because they are simply unaware of the effects their fluctuating hormones have on their performance.

Recommendation: Record ‘Day 1’ in a training diary so that training load can be synchronised to the body’s natural cycle. Likewise, keeping a good record of the symptoms experienced and the way the body responds to training during each phase of the cycle, will help significantly with planning training.

Effects on performance

Muscle growth

It is harder for women to build muscle due to their lower levels of testosterone than men. In addition, the female hormone oestrogen reduces the growing capacity of a muscle and progesterone increases the break-down of muscle during exercise.

Recommendation: Consume 20-25g of protein high in branched-chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine and valine) before exercise and within 30 minutes after exercise. Whey protein is rich in leucine and therefore ideal.

Metabolism and cravings

Oestrogen reduces the ability to burn carbohydrates, which is great for fat-burning during endurance events but means women should eat more carbohydrates before and during high-intensity training and racing. It also explains why women crave sugary foods during the high-hormone phase of their cycle.

Recommendation: Consume more carbohydrates during the premenstrual phase of the cycle, especially for long bouts of intense exercise (over 90 minutes). Aim for around 10-15g of protein and 40g of carbohydrates prior to long workouts. Then during the session, aim for 40-50g of carbohydrate (combined with protein and fat) per hour. Real food is preferable to energy gels.

Thermoregulation

Progesterone elevates core temperature, an effect that can usually be perceived by generally feeling hotter. In addition, during the high-hormone phase, lower blood volume reduces the body’s ability to sweat and therefore cool-down during exercise. Progesterone also makes the body lose more sodium which increases the risk of heat stress and hyponatremia[1] during endurance events in the heat.

Recommendation: Start hydration before exercise, particularly if it is in the heat. You can pre-load the night before a big session or event with a high-sodium broth such as chicken soup. There are also off-the-shelf products which will achieve the same effect.

Cramps and other gastrointestinal issues

During menstruation, the release of chemicals called prostaglandins make the uterus contract and expel its lining. This can be an uncomfortable if not painful process. Excess production of these prostaglandins can float around the body and trigger similar contractions in the bowels, leading to problems like gas and diarrhoea. In extreme cases they can even cause nausea and vomiting.

Recommendation: In the 5-7 days before your period starts, take 250mg of magnesium, 1g of omega-3 fatty acids (flaxseed and fish oil) and low-dose aspirin (80mg) before bedtime.

Bloating

Oestrogen and progesterone affect the hormones that regulate the fluid in the body. This is what leads to bloating during the days before hormone levels are high. Also the body retains more water and constricted blood vessels lead to a drop in blood plasma volume and cardiac output. So not only is it harder to fit into your regular clothes, exercise will feel harder.

Recommendation: (as per ‘Cramps and other gastrointestinal issues’ above)

Headaches

Some women suffer menstrual headaches, even migraines when oestrogen levels change. This usually occurs when hormone levels drop just before the start of a period. They are initiated by a change in blood pressure and sudden constriction of the blood vessels.

Recommendation: Stay hydrated and eat more nitric oxide-rich foods such as beetroot, pomegranates, watermelon and spinach in the days leading up to your period.

Heavy bleeding (Menorrhagia)

Women who have heavy periods are at a higher risk of becoming anaemic as their body is not able to replace the blood-iron stores as quickly as the blood loss. Athletes are at even higher risk due to their higher muscle stress, damage and inflammation from high cortisol levels following exercise. When cortisol is elevated, the liver creates more hepcidin, which reduces iron absorption. Anaemia can cause fatigue and shortness of breath, light-headedness and heart palpitations during exercise.

Recommendation: If you have any of these symptoms you should consult your GP and consider taking iron supplements.

I hope you find my research interesting and I am sure if you incorporate at least some of the recommendations into your training routine you will feel the benefit. If you need further help with optimising your training please get in touch.

Russell Gordon is the owner and cycling coach of inSync Cycling Coach. He helps cyclists of all abilities achieve their goals and he has raced road, time trial and cyclo-cross from regional to national levels. He holds TrainingPeaks Level 1 and British Level 3 cycle coaching accreditations.

References

Maud, P. J., Shultz, B. B. “Gender comparisons in anaerobic power and anaerobic capacity tests.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 20(2) June 1986: 51-54

Constantini NW1, Dubnov G, Lebrun CM. “The menstrual cycle and sport performance.” Clinics in Sports Medicine 24(2) April 2005: e51-e82.

Garcia AM, Lacerda MG, Fonseca IA, Reis FM, Rodrigues LO, Silami-Garcia E. “Luteal phase of the menstrual cycle increases sweating rate during exercise.” Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 39(9) Sept 2006: 1255-61.

Hutchinson, Alex. “The ‘last taboo’ in sports: The menstrual cycle” The Globe and Mail. Updated 12th May 2018. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/fitness/how-the-menstrual-cycle-influences-athletic-performance/article22989539/

Janse de Jonge. “Effects of the menstrual cycle on exercise performance.” Sports Medicine 33 (11) 2003: 833-51.

Janse DE Jonge, Thompson MW, Chuter VH, Silk LN, Thom JM. “Exercise performance over the menstrual cycle in temperate and hot, humid conditions.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 44(11) November 2012: 2190-8.

Moran, V. H., Leathard , H. L., Coley, J. “Cardiovascular functioning during the menstrual cycle” Clinical Physiology 20(6) November 2000: 496-504.

Sims, Stacy. “Roar”. Rodale Books, 1st edition ( August 2016).

[1] Hyponatremia is a low sodium concentration in the blood. Mild symptoms include a decreased ability to think, headaches, nausea, and poor balance. Severe symptoms include confusion, seizures, and coma.